Jonathan L. Friedmann, Ph.D.

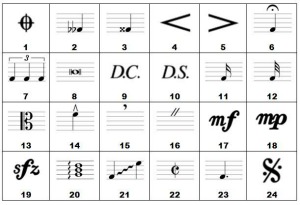

Fidelity to the score is a defining characteristic of classical music. Pitches, values, tempi, volumes, and articulations are clearly written for meticulous enactment. In translating these symbols into sound, the musician ensures the piece’s survival even centuries after the composer’s death. There is, of course, room for (slight) variation. Because elements such as dynamics and tempo markings are at least moderately open to interpretation, no two performances will be exactly the same. Still, the faithful and accurate rendering of notes is key to the integrity—and the very existence—of a classical piece.

The foregoing outlines the nominalist theory of classical music, which defines a work in terms of concrete particulars relating to it, such as scores and performances. Because a musical piece is an audible and experiential phenomenon, which is symbolically represented in the score, it can only truly exist in performance.

This position raises two issues. The first concerns “authentic” performance. Is it enough to simply play the notes as indicated, or do those notes have to be played on the instrument(s) the composer intended? Does a cello suite played on double bass or a reduction of a symphony played on the piano qualify as an instance of the same work? How essential is the use of appropriate period instruments? These questions look for elements beyond the written notes.

The second issue centers on the notes themselves. Most performances of concert works include several wrong notes. However, we generally do not discount these performances for that reason (and we may not register the wrong notes as they are played). If all of the notes are wrong, then the work has not been performed, even if the intention is sincere. But what percentage of the notes can be wrong for the performance to qualify as the work? We might argue that the work is independent from any performance of it; but that does not satisfy the nominalist’s position.

Most discussions of musical ontology—addressing the big question, “Do musical works exist?”—are confined to classical music. Score-dependent arguments do not lend themselves to jazz, for instance, where the improvising performer composes on the spot, or certain kinds of folk music, where embellishments are commonplace and written notation is absent.

Questions about music’s ontological reality do not have easy answers, and the various philosophical camps have their weaknesses: nominalists, Platonists (who view musical works as abstract objects), idealists (who view musical works as mental entities), and so on. Whatever fruits such discourse might bear, it points to the uniquely “other” nature of music, which is both recognizable and ineffable, repeatable and singular.

Visit Jonathan’s website to keep up on his latest endeavors, browse his book and article archives, and listen to sample compositions.