Jonathan L. Friedmann, Ph.D.

Felix Mendelssohn is credited with popularizing the use of a baton for orchestral conducting, beginning in 1829. Louis Spohr claimed he introduced the practice in 1820 while guest-conducting the large and spread apart London Philharmonic Society. Accounts of wooden batons appear before the end of the eighteenth century, but the device was slow to catch on, largely due to resistance from orchestras. Seventeenth-century ensembles were typically led by violinists (concert masters), who kept groups together by playing loudly, bowing vigorously, and occasionally tapping with the bow. Other tactics emerged as ensembles grew in size. In a 1752 treatise, C. P. E. Bach advised leading from the keyboard. When orchestras were first joined with choirs, the violinist would often lead one section, while the harpsichordist led the other. Opera conductors sometimes stood off to the side, pounding a staff on the floor. By the early nineteenth century, conductors positioned themselves in front of orchestras, brandishing rolled-up sheets of paper. They typically faced the audience, not the players, so as not to appear rude.

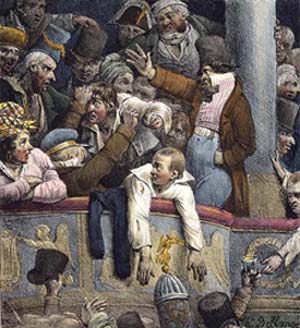

As this sketch suggests, the early history of conducting is not uniform or altogether clear. The stable position as we know it today masks a gradual and convoluted development. Mendelssohn was key in establishing the conductor’s independent role. According to Leonard Bernstein, a famously kinetic twentieth-century conductor, Mendelssohn founded the “‘elegant’ school, whereas Wagner inspired the ‘passionate’ school of conducting.” The two styles are not necessarily diametrically opposed: there can be passion in elegance, and elegance in passion. Nevertheless, they represent contrasting aesthetics, as outlined by Phillip Murray Dineen of the University of Ottawa.

The first is resident aesthetics, or functional beauty accrued from gestures associated with the music performed. These include fixed beat patterns and their modifications: accelerandos, ritardandos, fermatas, dynamic changes, and the like. The second is sympathetic aesthetics, or beauty derived from decorative contrivances apart from the task at hand. Dineen describes it as “a largely non-functional set of gestures unique to a given conductor, which often accomplish little or nothing mechanical in and of themselves, but instead either work to elicit a particular and specialized affect from the players or serve merely as interesting bodily motions for the aesthetic satisfaction of the audience.”

Bernstein is representative of the latter class. As music director of the New York Philharmonic from 1958 to 1969 (and conductor emeritus thereafter), he was praised and criticized for his ecstatic, dance-like style. His statement in The Joy of Music took some by surprise: “Perhaps the chief requirement of all is that [the conductor] be humble before the composer; that he never interpose himself between the music and the audience.” Gunther Schuller considered it “saddening and perplexing that Bernstein rarely followed his own credo.”

Of course, some music demands more exaggerated gestures than others. Compare, for instance, a quasi-spontaneous avant-garde composition with a predicable Classical chamber piece. In the former, demonstrative conducting is more functional than self-indulgent. Still, whether the movements are staid, effusive, or somewhere in between, the modern conductor adds an important visual dimension to a largely aural phenomenon.

Visit Jonathan’s website to keep up on his latest endeavors, browse his book and article archives, and listen to sample compositions.