Jonathan L. Friedmann, Ph.D.

Western classical music, as a generic term separate from the segmented musical chronology, has a quality of timelessness. Works spanning more than three-hundred years—from Bach to Stravinsky and beyond—are grouped together in concert halls, radio programs, and the public’s imagination. Judged as outstanding specimens of their kind, they exhibit wide stylistic variations and expressive techniques, yet reside comfortably side by side as “classics.”

Leonard Bernstein, speaking at a Young People’s Concert, pinpointed key contrasts between classical and other types of music: “The real difference is that when a composer writes a piece of what’s usually called classical music, he puts down the exact notes that he wants, the exact instruments or voices that he wants to play or sing them—even to the exact number of instruments or voices. He also writes down as many directions as he can think of, to tell the players or singers as carefully as he can everything they need to know about how fast or slow it should go, how loud or soft it should be, and millions of other things to help the performers to give an exact performance of those notes he thought up.” Contrastingly, Bernstein argued, “there’s no end to the ways in which [a popular tune] can be played or sung.”

Variations in classical performances stem not from self-initiated diversions, but from trying to interpret what the composer meant as closely as possible. Despite nuances of tempo, mood, and accentuation, the notes and instrumentation remain largely intact. These stabilized traits departed from the Medieval and Renaissance periods, when instrumentation was flexible, improvisation was integral, and notation was under-prescriptive. The meticulous directions and normalized expectations of classical music have ensured its transmission as a repeatable and recognizable art form.

Such timelessness comes into focus when confronted with its opposite. Beginning in the late 1960s, several attempts were made to “update” classical music for contemporary audiences. Switched-On Bach (1968) by Walter Carlos (now Wendy) initiated the trend with ten Bach arrangements for Moog synthesizer. Carlos followed it up with The Well-Tempered Synthesizer (1969), featuring electric versions of Monteverdi, Scarlatti, Handel, and Bach, and her soundtrack for Clockwork Orange (1972), with synthesized renditions of Beethoven’s Ninth. Part of the appeal of Bob Moog’s instrument was its contemporariness. Space Age listeners resonated with its “future is now” aesthetic and “orchestra-in-a-box” convenience. Elites were equally enthralled, handing Switch-On Bach three Grammys in the classical category: best album, best performance, and best engineered recording.

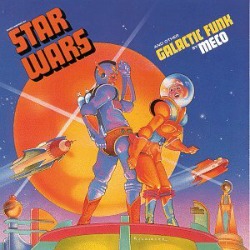

Meco’s disco album Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk, released in 1977 (the same year as the film), is an illustrative offering from that era of classical retooling. Its showcase piece, “Star Wars Theme/Cantina Band,” topped the Billboard Hot 100 for two weeks, owing to the popularity both of the film and of commercialized orchestral adaptations. Ironically, with his scores for Star Wars and other pictures, John Williams spearheaded a resurgence of classical film scoring, which had largely been replaced by pop soundtracks in the 1970s. Yet, as much as his writing convincingly retrieved an earlier genre of film music, it could not evade the sonic stamp of its age.

What unites these examples—and all pop treatments of classical music—is their time-boundedness. That which is “up-to-date” only remains so until that date has passed. The Moog sound is passé, disco is dead, but classical music is timeless. Its preservationist ethos—of instruments, interpretations, substances, and forms—has ensured its survival against the vicissitudes of taste.

Visit Jonathan’s website to keep up on his latest endeavors, browse his book and article archives, and listen to sample compositions.