Jonathan L. Friedmann, Ph.D.

Marxist philosopher Paul Mattick, Jr. once remarked that “art” has only been around since the eighteenth century. On the surface, this audacious claim seems to dismiss the creative impulse evident in hominids since the cave-painting days and probably before. But, really, the idea of art as something abstract or “for itself” is a Western construct with roots in the Enlightenment. That era gave rise to the notion of “the aesthetic” as a stand-alone experience, as well as individuals and institutions that actively removed artistic creation from organic contexts: critics, art dealers, academics, galleries, museums, journals, etc. Terms previously used in other areas, like “creativity,” “self-expression,” “genius” and “imagination,” were re-designated almost exclusively as “art words.”

Prior to this period (and still today in most non-European cultures) art was not a thing apart, but an integral and integrated aspect of human life. Sculpture, painting, ceramics, woodwork, weaving, poetry, music, dance, and other expressive mediums were more than mere aesthetic excursions. They beautified utensils, adorned abodes, demarcated rituals, told stories, and generally made things special. Skill and ornamentation were not valued for their own sake, but for their ability to draw attention to and enhance extra-artistic objects and activities.

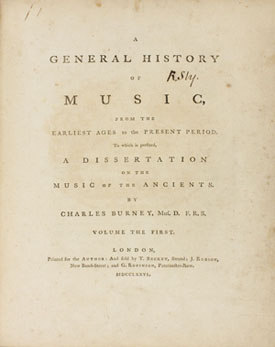

Eighteenth-century Europe witnessed the extraction of art from its functionalistic origins. It was segregated from everyday life and displayed as something of intrinsic worth. With this program came the panoply of now-familiar buzzwords: commodity, ownership, property, specialization, high culture, popular culture, entertainment, etc.

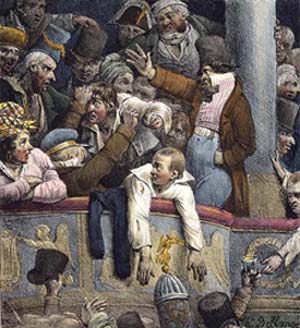

In the world of music, the contrivance of “absolute art” is even more recent. As New Yorker music critic Alex Ross explains, the “atmosphere of high seriousness” that characterizes classical concerts—with the expectation of attentive listening and quiet between movements—did not take hold until the early twentieth century. When public concerts first became widespread, sometime after 1800, they were eclectic events featuring a sloppy mix of excerpts from larger works and a miscellany of styles. Attendees chatted, shouted, scuffled, moseyed about, clanked dishes, and yes, even applauded (or booed) between (or during) movements. The performance was less a centerpiece than an excuse for a social happening.

As concert going morphed into a refined, bourgeoisie affair, the rigid format we are now acquainted with became the norm. Hushed and immobilized audiences sat in specially designed symphony halls and opera houses, which allowed composers to explore dynamic extremes hitherto impossible. “When Beethoven began his Ninth Symphony [1824] with ten bars of otherworldly pianissimo,” writes Ross, “he was defying the norms of his time, essentially imagining a new world in which the audience would await the music in an expectant hush. Soon enough, that world came into being.”

The impact of this development was wide-ranging. In no small way, it signaled the birth of music as an attraction in and of itself—a brand-new conception in the history of human culture. Like other artistic tendencies filtered through the Western consciousness, music was artificially detached from activities with which it had always co-existed. The radical break paved the way for the more general phenomenon of “music as entertainment” (highbrow, lowbrow and in between), and the commercialization and professionalization that came with it.

Visit Jonathan’s website to keep up on his latest endeavors, browse his book and article archives, and listen to sample compositions.